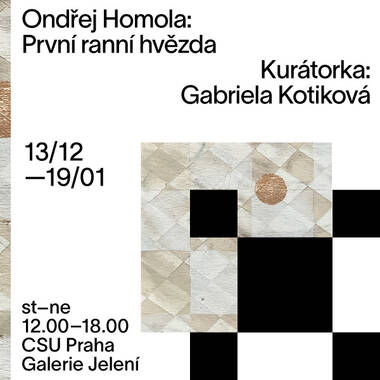

Ondřej Homola: Morning Star

13. 12. 2024 – 19. 1. 2025

opening: 12. 12. 2024 from 6 pm

curator: Gabriela Kotiková

GK: Ondra, I was intrigued when you mentioned in a recent interview that your ideas for paintings don't come about in the studio, but often at random moments during the day. So I’d like to ask you if it’s possible to record a visual memory or a feeling in a few words, or if you create a drawing or a photo that you later work from?

OH: Well, I have recently mentioned somewhere that I always carry notebooks in my pockets - and when I encounter that thing or feeling, I try to record it in words or a quick drawing. Sometimes I'll just jot it down in my notes on my phone, then in retrospect, I'll even surprise myself and shake my head in amazement because what happens is that the idea gets ripped out of that original place and time and then somehow it fades away and I don't even know what it was referring to anymore. Then it's usually replaced by something else and often something even more powerful. I also like poetry, it's been inspiring me a lot lately as well.

It seems to me that most of us live in a stereotype, a lot of visual experiences are repeated every day, we move around in the same places, we go to work back and forth the same way. And so it's not only a stereotype of activities, but also a visual stereotype. And it's only when you're travelling on a train, for example, that the brain suddenly becomes activated and has a different energy. And then, by staying in one place for a long time, that energy gets lost again.

It's true, I try to avoid that stereotype, in fact, just by choosing to work as an artist has resulted in none of the days I live are ever really the same. Similarly, I like to change my travel route once in a while, otherwise it would be the same every day. I also do that so there is the possibility for chance or surprise. I like change.

In exhibitions you usually work with the whole space, you create larger installations, but the image itself is still very important. Is it possible to say that you start by painting the image first, and only later do you give it the space and expand the field of its perception?

Most of the time I have an overall framework within which my topic moves.Then I look for the individual parts that try to support the ideas and layer the topic in a way that makes sense to me.I like to work with different perspectives on a subject, even with respect to the media.

You first exhibited at the Jelení Gallery in 2015, ten years ago, so it's an interesting comparison. At that time you worked a lot with installation, photography, collage, as well as video. But is it the case that over the years you have gradually become partially detached from new media and are not as interested in it as you used to be?

I feel like I'm currently fascinated by the physical existence of art, as well as the process. I'm interested in video and music, but it's probably not currently intertwined with something I want to communicate.

Can you compare how your approach to art has changed then and now? Was it that we were much more enchanted by new technologies then, as opposed to now, when we need to get away from them at least for a moment?

Quite possibly. Certain types of virtuality scare and fascinate me at the same time. But somehow, subconsciously, I crave the peace and balance I seek in an analogue approach to experience.

Another thing that has changed since then is that you now teach at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno, and together with Luděk Rathouský you head the Painting Studio II. So you often have to solve the problem of how to explain to students how to recognize a good painting and how to distinguish between better and worse quality. These criteria are difficult to formulate and are rather formed by experience, education, etc. But as an educator, you probably had to develop your own way of articulating this to students.

When working with students, we try to have a dialogue with them from the beginning. We don't push anyone, we don't bend anyone. Together we look for ways to develop their abilities in the best possible direction. The greatest joy and the ideal state is if the students eventually become the colleagues we meet in the field. I think it's important and good to keep our fingers crossed for each other somehow, because both artists and curators, as well as a number of other equally important jobs, that are sometimes invisible, co-create the fragile biotope of art, in fact the entire culture. Personally, I always try to have an empathetic perspective, it's an internal compass that I use.

When preparing the current exhibition at the Jelení Gallery, you talked about dealing with the theme of the morning star Venus and its pop culture reference and the meanings it carries. In your words, the exhibition is meant to be a poetic tribute to beautiful inspiration, the joy of actually being human...

Yes, sometimes I have a compulsive need to look at myself and my life from a distance. The star, even though it is an old and for many a forgotten symbol, offers just this perspective. It shines and looks down on us humans since the beginning of time. Stars don't care about our daily worries, our choices, us. Stars exist, and it seems like they will always exist, even if occasionally some of them fade away. They have no justifiable value to us. They were not created for the benefit of man. But people have always enjoyed watching them, describing them, studying them, or just appreciating them. Stars in general are a link to all the generations of people that have lived in this world, a visual language without words.

There is, among other things, a chessboard floor at the exhibition. This model of the chessboard has appeared several times in your earlier paintings... Is it also a symbol for you that has a specific meaning?

For me, the chessboard is a space for playing or an opportunity to look at things from two different perspectives. At the same time, I like the simple rhythm of black and white. And last but not least, I admit I like chess even if I'm not very good at it. I enjoy the game.

By painting the floor in this way and "elevating" it to the level of the other artwork on display, the gallery has become a compact space in which there are other objects on the floor and the visitors find themselves inside the artwork, unsure of where they can and cannot go. It is surprising how this relatively small intervention was enough to create such an intense feeling, and there was no need to build a complex exhibition architecture.

I enjoy working with minimal resources that can significantly change the outcome. I'm fascinated by the fine line between austerity and fullness. I like site specific work. Floors have long interested me both in architecture and as vehicles for history. I like their patina, it opens up space for imagination. A handprint in Altamira.

The exhibition also includes an antique cabinet. To what extent is it important for you to work with objects that have a history and memory? Just a glance into your studio shows interesting constellations of objects that, together with your paintings, create situations that could function as artworks and photographs.

I found this baroque wardrobe in a second-hand shop and I was totally enchanted by it. I was intrigued not only by the craftsmanship, but also by the atypical legs. I later found out that it was probably one of two pieces of furniture that served as a glasshouse for dishes. Despite its age, it never ceases to amaze me how anyone could make it. It's on display as a reminder of the generations that came before us.

I was also intrigued how you talked about the fact that you want to communicate through your exhibitions the belief that life can be beautiful, despite all the things we are tested by as human beings. In the sense that you want to give people the opportunity to explore everyday experiences from a different perspective. You've said outright that your art is also about looking for the little things and praising them. I find this to be an important idea in this day and age, where artists often feel they have to teach, explain and fix the world through art.

I see trying to explain and fix the world as a part of the artist’s job, and I think it actually shows the humanistic conviction of those who seek to do so, we are in this together. Art can certainly change the world, but I feel, and many may disagree with me, it does so somewhat slowly and with a time lag. Art instantly changes the active actors - it changes us, who are doing it for someone else, and only then the recipients. We learn and experience along the way, and only on the basis of the experience, we can change our current point of view.

I am afraid, though, that until the majority of our society accepts the overall cultural life as an important component and part of its life, it will continue to be difficult to articulate the burning issues through art. But I believe that despite these efforts, it is important not to lose the joy from art, creation and presence.

Yes, I feel that in these times of wars and environmental problems and everything that's going on, it's valuable for art to allow us to stop and focus, and also to have a more subtle sensitivity to the world around us. And that can ultimately be more helpful than it may seem.

Of course, all these unfortunate circumstances actively surround us. It's hard not to get trapped in our bubbles. Sometimes I feel like these disasters are catching up with us, and the waters are rising, the island is shrinking, and we are losing our sense of imaginary stability through the salami-slicing tactics. Knowing all this, I would like to try to share at least a small glimmer of my show's ordinary and fragile hope.

The program of the Jeleni Gallery is possible through kind support of Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, Prague City Council, State Fund of Culture of the Czech Republic, City District Prague 7,

GESTOR – The Union for the Protection of Authorship

Media partners: ArtMap, artalk.cz, jlbjlt.net and ArtRevue